It’s nearly four months since Boris Johnson told MPs that the government’s test, track and trace operation for coronavirus (Covid-19) would be “world-beating”.

But in the Commons Liaison Committee on Wednesday 16 September, the prime minister acknowledged the situation was not “ideal”.

He didn’t have much choice. Demand is vastly outstripping capacity and across the country. People have described travelling hundreds of miles to get their children tested.

Labs “overwhelmed”

Meanwhile reports suggest a surge in the number of swabs is overwhelming testing laboratories. Far from being the envy of the world, Labour’s Wes Streeting told health secretary Matt Hancock in the Commons this week that the system was:

a bloody mess.

Back on 20 May, Johnson told the Commons:

We will have a test, track and trace operation that will be world-beating, and yes, it will be in place – it will be in place by June 1.

But as that deadline came around, reports emerged of a massive failure to reach people whose recent contacts had experienced coronavirus symptoms. Meanwhile, call centre contact tracers had so little work to do, they were essentially “paid to watch Netflix”.

It’s literally never worked

The system has repeatedly failed to meet the government’s target of reaching 80% of close contacts of people who have tested positive for coronavirus. The government had stopped widespread community testing on 12 March because it was overwhelming capacity. That was just before lockdown.

Mobile test centres were set up, including in hotspot areas. But people keen to avoid quarantine by proving themselves virus-free swamped the sites.

This week, Johnson has again mentioned plans to prioritise who should be able to get a test. This means that even those with symptoms may still not be able to get a test. Meanwhile, Hancock claims that people without symptoms using the system is “inappropriate”, and makes it harder for genuine potential carriers to get tested. This is despite the fact that many coronavirus carriers don’t have any symptoms.

And still, whole school year groups, frontline workers and families have had to isolate because they couldn’t get a test.

“We don’t have enough capacity”

Johnson admitted the problems with the system on Wednesday, telling MPs on the Liaison Committee:

We don’t have enough testing capacity now because, in an ideal world, I would like to test absolutely everybody that wants a test immediately.

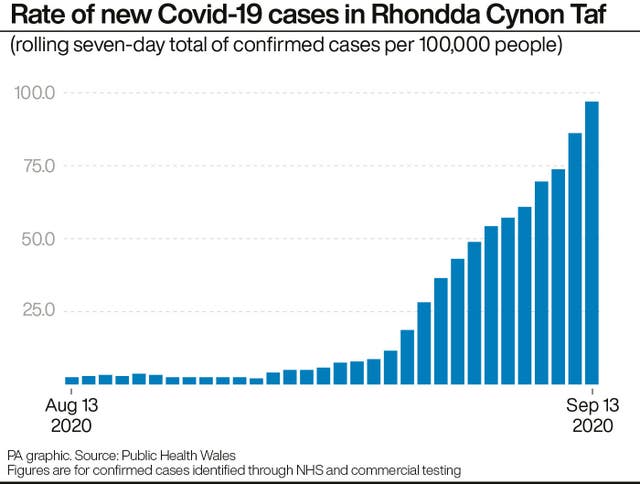

Instead, the government is looking at other ways of trying to halt the spread of coronavirus. They include strict new measures in Covid-19 hotspots, such as parts of the north of England, and a short-term lockdown for Rhondda Cynon Taf in South Wales.

Ministers are also considering plans to limit social gatherings, including a possible 10pm curfew for pubs and restaurants, on top of the “rule of six” restriction on get-togethers announced this week.

“Losing our ability to accurately track the virus”

Adam Kucharski, a scientist and government adviser, warned the shortage of testing capacity is affecting the authorities’ ability to track the spread of the disease.

He told the BBC Radio 4 Today programme:

I think we are getting to the point where potentially we are losing our ability to accurately track the virus.That means that we could have a situation where it is getting into risk groups, we start to see more cases appear and we don’t have good warning of that.

It also affects our ability to have more targeted, nuanced measures. If we lose the ability to track the virus it ends up that more blunt tools will be deployed. That is what we saw earlier in the year.

“Operational challenges”

The government says anyone with symptoms needs a test. But the health secretary said this week that there are “operational challenges” with testing.

He insisted the average distance travelled to a test site is now 5.8 miles, adding it is “inevitable” that demand rises when a “free service” is available.

The government is drawing up plans to prioritise who should get a test, starting with people who have acute clinical need and those in social care settings.

Hancock also claimed there had been an increase in demand among people not eligible for tests in recent weeks. But there is no data to support this.

Test slots add strain to A&E

A negative test result can bring an end to self-isolation for people who think they may have coronavirus. It means people in quarantine should be able to return to work, school, or at least, leave their homes.

But one of the problems is the lack of testing capacity, which is particularly worrying in areas where coronavirus is most prevalent.

Research by the PA news agency this week identified that testing slots were offered in only one of the 10 local authorities with the highest Covid-19 infection rates.

NHS Providers, which represents NHS trust leaders, expressed concerns that shortages were leading to an increase in people attending accident and emergency units requesting a test – something hospital bosses have urged people not to do.

Blaming the public?

Last week, Hancock appeared to blame people without symptoms seeking tests for the squeeze on resources. The Department of Health and Social Care also appealed to those without symptoms not to get a test.

That is despite official government guidance published the previous month – and still available online – that says testing people who don’t have symptoms can have “useful public health benefits”. It can detect cases before people enter a high-risk setting such as health or social care, or “where there is strong reason to believe there is a high level of coronavirus present”.