As the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement continues to make waves and hold racist power structures to account, the marketplace of ideas is thriving. People wanting to reduce racism to a debate and consider ‘both sides’ insist that while racism is bad, vandalising statues is arguably worse.

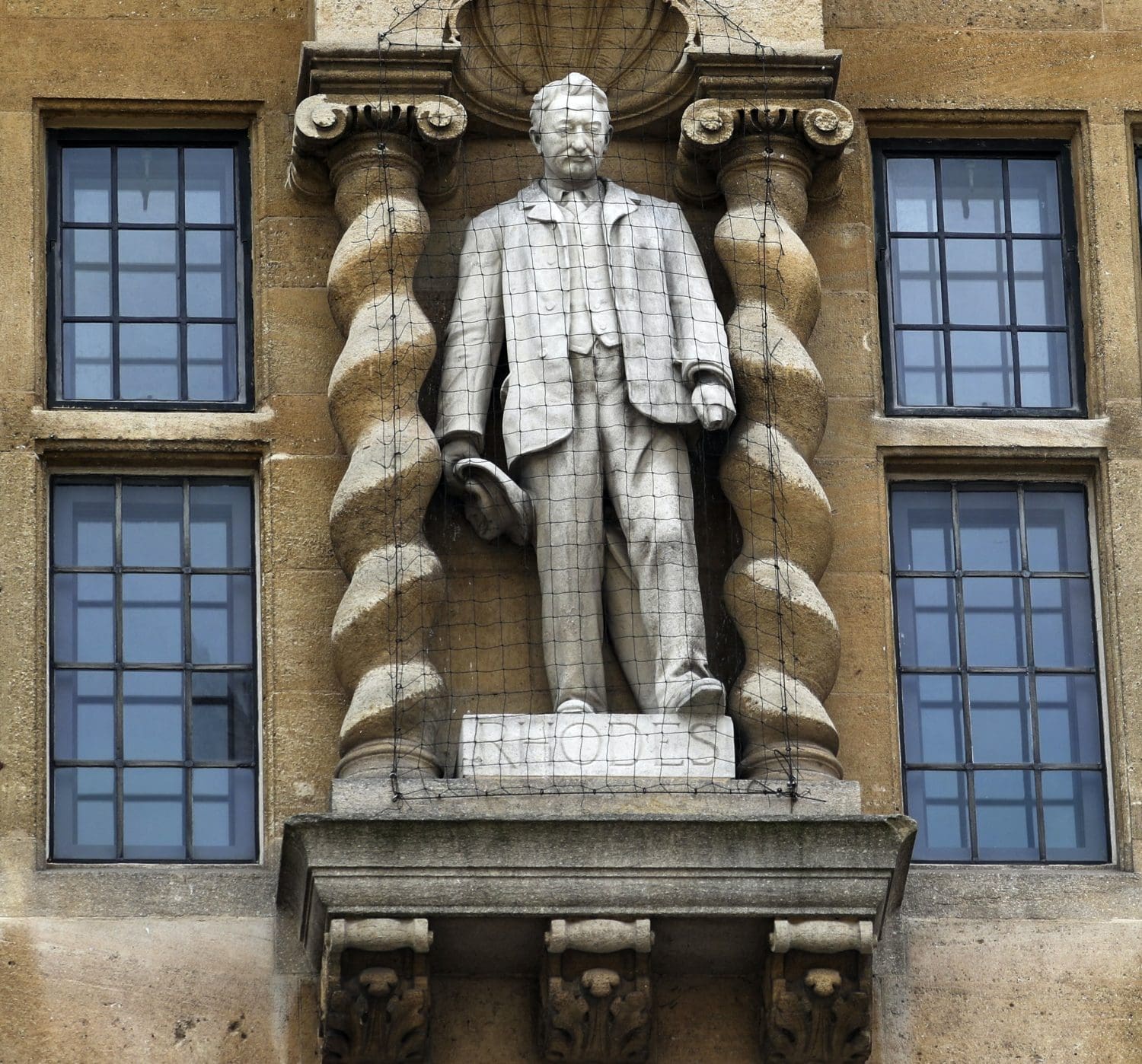

The prime minister expressed his views (behind a paywall, of course) saying we can’t “photoshop” history by removing figures we don’t agree with from our public spaces. Launching into a defence of former PM Winston Churchill, Johnson gives an impassioned argument for why Churchill’s statue should remain standing in Parliament Square.

Gaslighting

But Johnson’s bad-faith arguments are as breathtaking as they are insulting. In fact, they probably amount to what could be described as gaslighting – an abuse tactic often employed by narcissists. This is because demanding the removal of statues of racist figures, including Churchill, is actually about not wanting to “photoshop” history. It’s about demanding that we acknowledge Britain’s racist colonial past, and the people it harmed. It’s about removing the label of ‘hero’ from someone like Churchill who is guilty of a number of heinous crimes against People of Colour, including, but not limited to, genocide.

To call such a man a hero, despite his well-documented record of white supremacist oppression, is the very definition of photoshopping history.

What’s a greater cause for concern, however, is the sheer number of people in Britain who agree with Johnson’s viewpoint; those who believe Churchill was an anti-fascist hero rather than a proud white supremacist. These people aren’t limited to the far-right either – they seem to lie across the political spectrum. And it’s these very people who prove why Britain so desperately needs to be re-educated on its history in the manner that the BLM movement is seeking.

BLM activists aren’t the ones who want to revise history – in fact, it’s the opposite. They want to correct the revision of Britain’s colonial past that’s been propagated through the education system and popular discourse so far. The photoshopping Johnson is decrying has already taken place. BLM activists are now seeking a truer, more accurate picture of history. Because we can’t address racism in the present if we don’t acknowledge its roots in the white supremacist system of colonialism.

Then and now

It’s important to recognise that politicians saying ‘Black Lives Matter’ means very little if they don’t stop to address the origin and root cause of racism. The roots of racism lie in white supremacy as an ideology – but this doesn’t just mean swastikas or burning crosses. It means eugenics – the field responsible for ‘race science’ and notions of humanity, intellect and spiritual worth being tied to hereditary traits. (Incidentally, Johnson’s top adviser Dominic Cummings’ notions of wealth being linked to educational attainment are grossly eugenicist). Although the term ‘eugenics’ wasn’t coined until 1883, the idea of some people being superior dates back to the ancient Greeks. Eugenics formed the pseudo-scientific foundation for white supremacy. It informed the belief in the superiority of white people and their entitlement to appropriate foreign lands from ‘savages’, which then led to the colonisation of non-Western nations.

And the crimes of colonisation are many. Along with land appropriation, it resulted in the slave trade, famines, genocide, and mass looting of natural resources which led to poverty so crippling it’s still felt in ‘developing’ nations today. It also resulted in the decimation of native languages and cultures, as well as the desecration of spiritual symbols and destruction of cultural artefacts.

People may argue that what happened in the past can’t be changed, so we shouldn’t be angry about it now. Indeed, we can’t change the past – but if we never talk about what happened, we won’t learn from it either. Racist stereotypes about Black people and other People of Colour emerged in the wake of eugenicist ideas about race. And the association with criminality persists to this day. The dehumanisation persists to this day. The notion of moral inferiority persists to this day. So many preconceived ideas about People of Colour, which create a hierarchy of who is and isn’t deserving of due process, dignity, and basic rights, persist to this day as a result of the colonialism Western nations don’t want to talk about.

Structural racism

So we can neither talk about nor effectively address ‘structural racism’ today without acknowledging, loudly and openly, the role colonialism played.

It’s what’s playing a part in Windrush citizens getting deported, even in defiance of court orders.

It’s what leads to People of Colour being criminalised at disproportionate rates.

It’s what leads to increasing deprivation for the poorest BAME communities.

It explains why People of Colour aren’t listened to or granted admission to hospital when needed, potentially resulting in a higher number of coronavirus (Covid-19)-related deaths.

And when we learn that the police force in the US emerged as a continuation of racist ‘slave patrols’, present-day police brutality begins to make more sense.

So this is why BLM activists are demanding that statues of slave owners and white supremacists are removed from public spaces. At the heart of this demand is a need for Western nations to take responsibility for the crimes of their colonial, white supremacist past. And this conversation would probably never have happened if BLM activists hadn’t thrown that statue of slave trader Edward Colston into the river.

Conversations about racism and white privilege are rarely easy. It’s uncomfortable for white people to accept that they might still be benefiting from a system that they played no active role in setting up. It’s easier, instead, to talk about ‘diversity and inclusion’ or ‘unconscious bias’. However, while the injustice of racism is casting a shadow on the present, it’s rooted in the past. Equality, diversity, inclusion, unconscious bias – none of these are effective tools in addressing the deeply rooted, systemic injustice that Black people and other People of Colour have been subjected to for centuries. We can only bring justice to victims of racism, and begin to address racism effectively, if we tear up these roots. It’s not an easy task, but it is a necessary one.

Featured image via Wikimedia