The hepatitis C virus (HCV) chronically affects up to 150 million people worldwide. In the UK, an estimated 0.5% of the populated are affected. If left untreated, the virus can lead to severe liver damage and sometimes liver cancer. In 2014, two drugs were approved that offer a more than 90% cure rate for HCV; However, the NHS this week have been accused of disobeying guidelines and rationing their use. Is this the fault of the NHS? Or a greater issue with company pricing for new-to-market drugs?

HCV is transmitted through infected blood. It’s main route of transmission is through the sharing of needles by infected individuals, although historically the virus has also been known to spread through blood transfusions, sharing razors or toothbrushes, and, rarely, through intercourse.

Previously, HCV has been treated with a long-winded multiple-therapy approach and cure rates ranged from 30 – 90% for the most common strain of the virus (genotype 1) in the UK.

However, in 2014 two new Direct Acting Antivirals (DAA) drugs were approved, which have cure rates of more than 90%, and the potential to revolutionize HCV treatment.

Brief history of improvements in genotype 1 HCV treatment:

- 1980’s – 1990’s: Treatment with interferon for 48 weeks. Cure rate of ~9%

- 1998 – 2000’s: Interferon plus ribavirin for 48 weeks. Cure rate of ~30%

- 2002 – 2010: Pegylated interferon plus ribavirin, for up to 48 weeks. Cure rate of up to 51%

- 2011: “Triple therapy” approved. Pegylated interferon, ribavirin, and protease inhibitors given together, for either 24 or 48 weeks. Cure rate rose to 66 – 88%

- 2012: Direct Acting Antivirals (DAAs) were approved, given in combination with pegylated interferon for 12 or 24 weeks. Cure rate of up to 90%

- 2014: DAA-only therapies were approved. Treatment time reduced to 8 to 24 weeks. Cure rate of more than 90%

High efficacy, but high cost

The prices of the drugs – Sovaldi and Harvoni, manufactured by Gilead Sciences – range from around $90,000 per patient in the US to almost £35,000 in England and 41,000 euro in France.

In other words, they are extremely costly, which has sparked global debate about access to high priced therapeutics for governments with limited resources.

NHS England, unable to budget for broad access to these drugs, has been accused this week by researchers from the University of Cambridge, the University of Bath and The BMJ of defying the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)’s authority by trying to alter the outcome of the NICE process. The investigation was published this week by The BMJ.

The investigation revealed that apparent panic over high prices and affordability seemingly led NHS England to employ many delaying tactics, which succeeded in hampering timely access to these drugs. The result is possibly disastrous consequences for some patients.

Andrew Ustianowski, a consultant in infectious diseases at Pennine Acute Hospitals NHS Trust, says:

I think some people in NHS England would love to clip NICE’s wings and turn it into a kind of recommendatory rather than mandatory body. And if you are going to choose a fight then choosing this battlefield is quite a sensible thing to do – a marginalised population, very high-cost drugs.

Dr Ustianowski resigned from NHS England’s clinical advisory group, in protest at deliberate attempts to delay access to treatment. He told The BMJ:

I didn’t want to be associated with what was happening

Similar scene in the US

The US has experienced similar problems to those being brought to light in the UK.

In 2015, the HCV treatment scene in the US was driven by the high cost of HCV medications and the restrictions placed on access to the drugs to treat the virus.

Another issue for patients in the US was the continued severe access restrictions that had been put in place by insurance companies and Medicaid – the US’s social health care program – since 2013. The high cost of the medications was a large part of the problem, combined with the number of people who would have to be covered: An estimated 2.7 – 3.9 million people in the US have chronic hepatitis C and in 2014 there were around 0.7 acute cases of the disease per 100,000 population.

The high cost of the drugs has led to exclusivity deals between pharmaceutical and insurance companies to reduce the cost of medications. This means that, effectively, the medical decision-making process is now being made by pharmaceutical and insurance companies, rather than primary care providers.

This in turn has led to patients importing generic HCV drugs produced in countries other than the US. Since 2015, lawsuits have started all over the country, challenging Medicaid and insurance denials.

US medical professionals are hoping that these lawsuits will lead to easing of the restrictions, enabling more access to the medications for patients.

What’s the real issue?

Is the inability to obtain access to these higher priced drugs really a problem of the NHS? Or is there a bigger problem with company pricing?

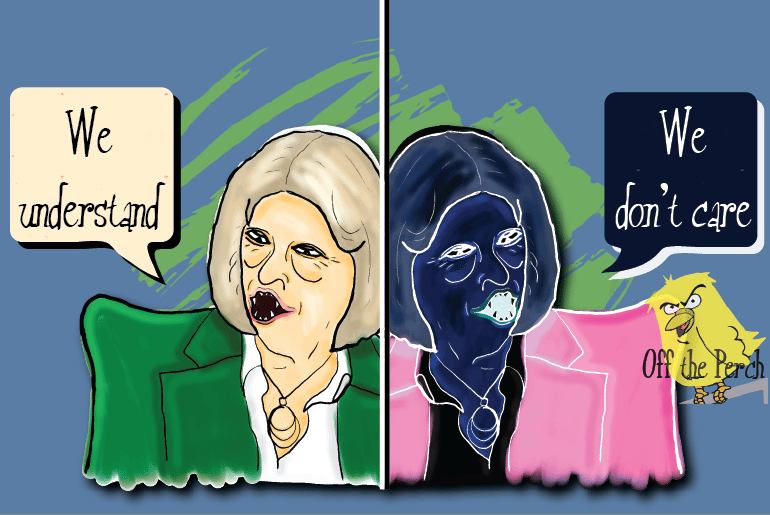

NICE did eventually succeed in publishing guidance recommending the new drugs for the majority of hepatitis C patients. But NHS England is still not fully following NICE’s mandate, which requires that approved drugs are made available within the NHS.

Instead, NHS England has restricted use of the new drugs by forcing quotas on clinical teams around the country.

This rationing has left many clinicians facing hard decisions and difficult conversations with patients who have already seen their treatments delayed several times. And there is now growing evidence that, as is happening in the US, some frustrated patients are turning to overseas sources to get the drugs at their own expense.

NHS England claims that its delivery of drugs is entirely within the parameters of the NICE guidance. It highlighted Gilead’s pricing as the key reason why treatment was being delayed, echoing the major criticisms of Gilead’s pricing strategy in the US.

Despite “exploring the potential for a longer-term strategic procurement for a supply agreement with the industry to improve affordability of and access to treatment”, NHS England argues that, under current rules, it is not able to negotiate specific deals with individual drug companies.

Furthermore, with the majority of NHS Trusts ending up in the red in 2015-16, prompting renewed claims that the government is underfunding the NHS, the fact that NHS England have resorted to rationing of the new drugs perhaps does not come as a surprise to many.

Advocacy groups speak out

The Hepatitis C Trust, a patient advocacy organisation, believe the NHS is risking legal action over its decision to ration the new drugs.

Its chief executive, Charles Gore, has said:

[The Trust has] already spoken to solicitors to take on any cases that come up, because we are not going to have NHS England pick on a disenfranchised group

Researchers argue that the acquisition strategies of drug companies magnify development costs and leave the public paying twice – for research and high priced medicines.

Solutions, the advocacy group say, include giving health systems increased power to negotiate pricing and payment models, limiting share buybacks, and testing other ways to encourage and reward drug development.

Featured image via Flickr / ANSES (image cropped)